Tag: product development

-

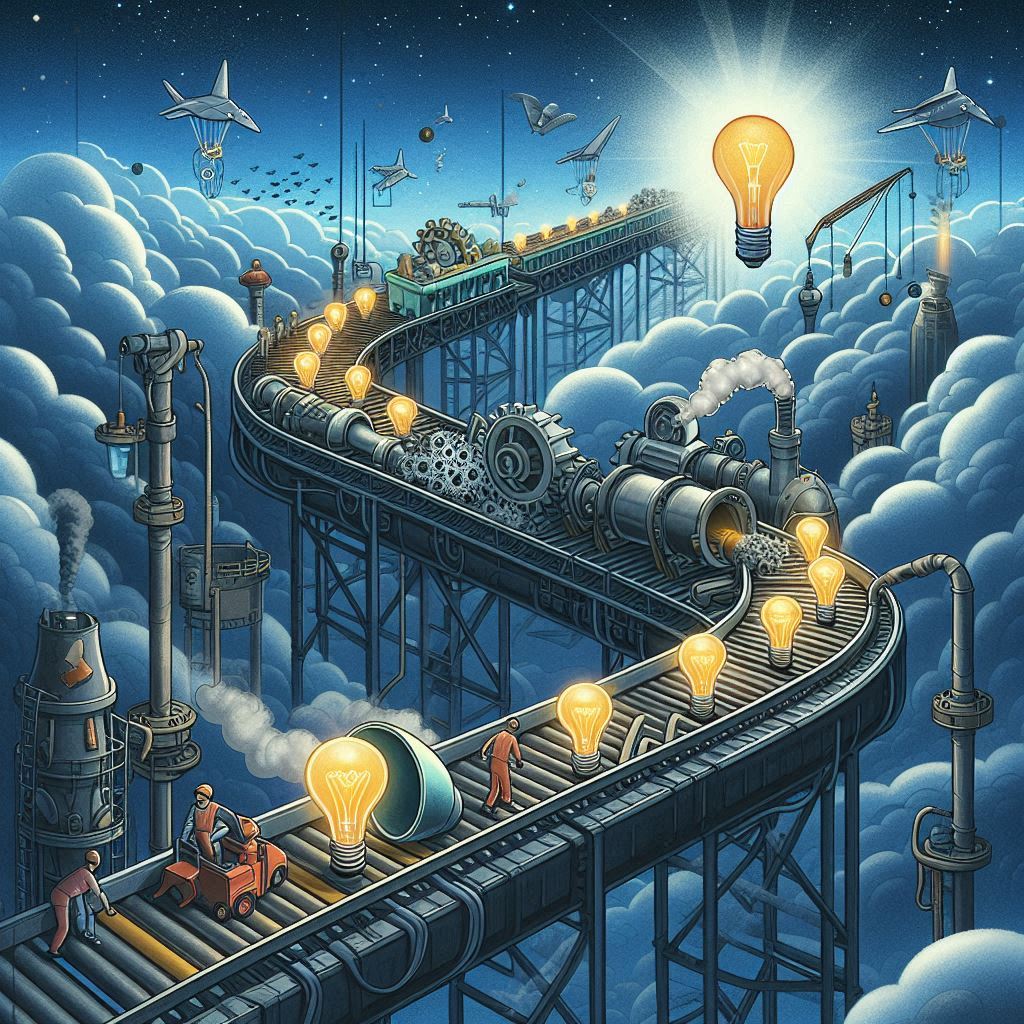

The Three Risk Traps Blocking Innovation

Many valuable innovative solutions get stranded due to the perceived risk of adopting them. Risk should be an important component in all decisions, but it might be counterproductive if it is not put into proper context and perceived adequately. There are especially three risk perception traps that block innovations. Understanding them might help to unlock…

-

Stuck in beta?

Experimentation is good but also deceptively simple. Even though the experiments can be incredibly complex and the brightest minds are involved, from an organizational perspective it is simple: you just select a problem, and then you get a budget and then you solve it. But even though you can feel and taste the solution it…

-

From the Super Bowl to Super Products

Later this evening Super Bowl XLIX is played. One of the teams playing has reached it more frequently than any other team in recent decades. The Patriots are a remarkable team, that we could learn a lot from about product development and winning against the competition in a highly competitive market (disclaimer – I always…

-

What is a successful product?

Every company wants to be a success. One key ingredient in that is successful products. A successful product will look different to different companies, but usually it can be tracked by KPIs. For any business it is very important to find the right KPI and be wary of so called vanity metrics. What’s your “On…

-

How to manage a globally distributed product team

Building a product alone is difficult. Building it with a team is harder, but building it with a distributed team is even harder. Still, today it is rare that any company is building any product with a 100% local, in-sourced on site team. That is why one key ability in building a succesful product is…

-

Experimentation in product management

Traditionally new products were developed according to the founder’s idea that was written down, which the engineers built. The last few years this pattern has changed. Across the internet there has been a shift in mindset to bring the customer into what we are building. There is a growing awareness that we are wrong about…

-

What product development strategy is right for your start up?

There are two primary product development strategies and multiple ways of executing them, but there is only one that is right for your company. Finding that strategy and understanding the dynamics may be the difference between success and failure. It may also revert your perception of whether you are doing well. Nicholas Nassim Taleb has…

-

From User Interface Design to Virtual Product Design

User interface design is very important for any company who has virtual products, but when more and more people access virtual products through more and more different user interfaces it becomes increasingly important to not design the entire virtual product. Not just the user interfaces. Not just the user interface I have been researching how…